‘Talk to any child with gay parents, especially those old enough to reflect on their experiences. If you ask a child raised by a lesbian couple if they love their two moms, you’ll probably get a resounding “yes!” Ask about their father, and you are in for either painful silence, a confession of gut-wrenching longing, or the recognition that they have a father that they wish they could see more often. The one thing that you will not hear is indifference.’

‘Talk to any child with gay parents, especially those old enough to reflect on their experiences. If you ask a child raised by a lesbian couple if they love their two moms, you’ll probably get a resounding “yes!” Ask about their father, and you are in for either painful silence, a confession of gut-wrenching longing, or the recognition that they have a father that they wish they could see more often. The one thing that you will not hear is indifference.’

So wrote Katy Faust in ‘An open letter from the Child of a Loving Gay Parent’ last year.

I was reminded of her letter when reading a new research paper by American sociologist, Paul Sullins, on same sex parenting. This latest research uses a large US national survey, and found that at age 28, adults raised by same sex parents were at over twice the risk of depression as those raised by a mother and father. Elevated risk for obesity, suicidality and anxiety was also found.

These findings seem to correlate with the personal experiences of, say, Katy Faust, and Robert Oscar Lopez [pictured above], both raised by (loving) same sex parents.

But rather than just citing personal experiences, what can we draw from this new research?

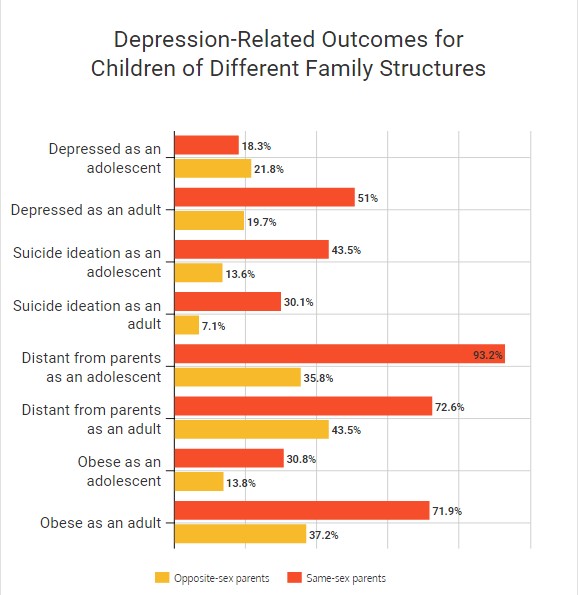

- Sullins found that that in adolescence, children of same sex parents were marginally less depressed than the children of opposite-sex parents (most research has been on this age group and younger children). However by the time they were young adults (24-32 years) their experiences had dramatically reversed and over half were depressed. The proportion went from 18% to 51%. Conversely, Sullins found that children in opposite sex families went the opposite way, and the proportion who were depressed dropped (albeit slightly) from 22% to 19%.

- Both groups of young adults showed increases in the proportion that were obese from when they were adolescents to becoming young adults. But the differences between the two groups were significant, with 31% obesity among young adults with opposite sex parents, compared to 72% of those from same sex households.

- 73% of young adult children of same sex parents felt ‘distant from one or both parents’ compared to 44% of young adults in opposite sex households (see graph below).

- Sullins suggests that because suicidal thoughts, missing a parent and obesity are much more prominent among the same sex parented group, this could account for the higher rates of depression.

- Lastly, Sullins reminds us that, as with all observational studies, causal inference is not possible and his findings should be considered only provisional and exploratory until and unless they are confirmed by further research.

In other words, do not exaggerate the findings nor dismiss them out of hand.

And yet because they run counter to most other main-stream research on same sex parenting, many do dismiss these findings. The journal the research is published in is not recognised as a particularly prestigious academic journal, the author warns us to interpret the results with caution and it has received very little publicity (not surprisingly in view of its ‘politically incorrect’ findings).

So can we trust this research or not?

Sullins used data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, a very large on-going national survey. Because it is longitudinal it evaluates the same people over a long period of time. While it uses data from a large population survey of over 15,000, because the actual number of long-term same sex couples in the population who have adolescent children is so small, the sample numbers are inevitably small. Sullins was also very careful to exclude couples in which an opposite sex parent was still involved (many other surveys have not done this, and have thus concluded ‘no differences’). This left Sullins, through no fault of his own, with 20 couples. Hence his warning to interpret the results with caution.

Nevertheless, the significance of the different findings between the groups remains. So we can still learn from them. His is also the first study to follow a cohort of such children into adulthood.

The fact that the research was published in an open access peer reviewed medical journal may well have been to ensure it was available for free to all, quickly, and was not tied down by a politicised peer review process (which can often be biased). Unfortunately, this could mean it is deemed to have less academic authority – but that does not necessarily mean less accuracy.

There are weaknesses with all research on same sex households. I have previously showed how much research on such households is unrepresentative (unlike this research), uses small samples (like this research), does not consider the views of older adolescents, let alone young adults, and frequently relies on parental self-reports (unlike this research). It is surely common sense that some of the problems children may have with same sex parents will not appear until they are in early adulthood, and that parents will have different perspectives to their children. It is not enough just to look at whether the children are ‘no different’ as children, we have to look at how they turn out in adulthood.

This is not the first paper on same sex households by Sullins. Last year he published another peer reviewed article in the British Journal of Education, Society and Behavioural Science, concluding that:

‘Emotional problems were over twice as prevalent for children with same sex parents than for children with opposite sex parents’.

Contrary to popular opinion, this risk was unaffected by stigmatisation. The research was based on 512 children with same sex parents, using the US National Health Interview Survey.

Prof Regnerus has found that adult children who had been raised, for at least a brief time, in families with a gay, lesbian, or bisexual parent were more likely to report dysfunctional adult outcomes than those who had been raised in other family structures, especially families with continuously married heterosexual parents.

Prof Regnerus defends his own work, saying that: ‘People think I have it in for the LGBT community(ies). I do not. I have it in for a science that refuses to proceed honestly… I may be unpopular…but about the comparative advantages of stably married households with mom, dad, and children, I am not wrong. It will take more than smoke, mirrors, and shifty rhetoric to undo the robust empirical truth.’

He says of himself and Sullins: ‘We have seen the data and we are convinced that they cannot sustain the “no differences” thesis’.

The problem now is that this research has become a political and social issue, when it should be about robust empirical truth and not hiding or ignoring research that does not fit political agendas.

This research is not an ‘attack’ on same sex parenting per se. As Regnerus says: ‘Same sex parents are as warm, caring and loving as any other sets of parents, and are probably good parents as individuals, but they cannot supply for the child the emotional or psychological benefits of the missing father (if lesbian parents) or mother (if gay male parents).’

In other words, just as Katy says in her letter, this is not about the parents, this is about the missing parents in same sex households. However loving they are, two same sex parents cannot provide what an equally loving mother and father can provide.