A new study has found that a common form of infertility treatment increases the risk of children developing autism and mental disabilities in later life.

A new study has found that a common form of infertility treatment increases the risk of children developing autism and mental disabilities in later life.

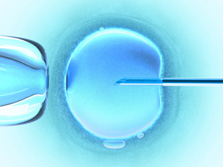

Intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) involves injecting one sperm directly through the shell of an egg and depositing it inside. It is used when sperm quantity or quality is not sufficient to achieve fertilisation through normal intercourse. The major advantage of ICSI is that as long as some sperm can be obtained, even in very low numbers, fertilisation is possible.

ICSI is increasingly popular in the UK with around half of fertility treatment cycles in the UK using it. The number of babies born in the UK through using ICSI has steadily increased since it was introduced in 1992.

This latest research reports that children born following ICSI are 51% more at risk of developing intellectual impairments than those born by normal conception.

The study by researchers at Kings College London Institute of Psychiatry and the Karolinska Institute in Sweden, looked at data on 2.5 million children born in Sweden from 1982 to 2007, of which 30,959 were born as a result of IVF. They conclude:

‘Compared with spontaneous conception, IVF treatment overall was not associated with autistic disorder but was associated with a small but statistically significantly increased risk of mental retardation. For specific procedures, IVF with ICSI for paternal infertility was associated with a small increase in the relative risk for autistic disorder and mental retardation compared with IVF without ICSI. The prevalence of these disorders was low, and the increase in absolute risk associated with IVF was small.’

A news article fleshes out the detail a bit more, explaining that among children conceived following IVF with ICSI, the risk of mental disability increased by 51% compared to natural conception, with 93 out of every 100,000 developing a mental disability.

In the UK this would be equivalent to 22 of the 24,000 babies born each year using IVF with ICSI having an intellectual disability (defined by an IQ below 70 and an inability outperform every day skills such as learning, communication or social relationships). Among children conceived naturally the risk of mental disability was 62 out of every 100,000 births.

The absolute numbers affected may indeed be small, however in 2012 the total number of babies born worldwide as a result of IVF technologies was around 5 million. These numbers will continue to increase with around 350,000 babies born annually as a result of an estimated 1.5 million IVF cycles.

If approximately half of IVF treatments now use ICSI that would be 2.5 million treatments undertaken worldwide. And with around 93 cases of mental disability per 100,000 ICSI births then around 2,325 children will develop it every year.

Of course these are approximations and generalisations. But what is interesting is that this new study is just the latest of several highlighting real risks with the use of ICSI (and sometimes ‘standard’ IVF too).

Last year a large study from Australia found a significantly increased risk of handicap for children born using ICSI. It found that one in ten children conceived using the fertility treatment ICSI have birth defects. (cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, urogenital, and gastrointestinal defects and cerebral palsy. Minor defects were generally excluded, with the exception of those that require treatment or are disfiguring. Diagnoses were coded according to the British Paediatric Association modification of the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9)).

The Australian research followed 1,000 babies born by IVF or ICSI for five years, and followed 500 five-year-old children who were conceived naturally. The unadjusted risk of a birth defect was 5.8% following natural conception, compared with 7.2% following IVF, and 9.9% after ICSI. In the case of ICSI, but not IVF, the increased risk of birth defects persisted after adjustment for maternal age and several other risk factors.

The HFEA produces long-term data on fertility treatments so I did a quick calculation of their figures for numbers of live babies born using ‘micro-manipulation treatment’ (99% of which are through using ICSI, none through IVF).

Between 1992-2005 there were approximately 37,800 babies born using ICSI. It does not take a good mathematician to work out that, in the UK alone, one in ten would give a rough total of 3,700 babies born with birth defects as a result of ICSI up to 2005. (If these had been natural conceptions then under 2,200 births with abnormalities would have occurred).

The Australian journal article warns: ‘Although the large majority of births resulting from assisted conception were free of birth defects, treatment with assisted reproductive technology was associated with an increased risk of birth defects, including cerebral palsy, as compared with spontaneous conception. In the case of ICSI, but not IVF, the increased risk of birth defects persisted after adjustment for maternal age and several other risk factors.’

So why might using ICSI carry these extra risks of mental and physical handicap?

The risks may well stem from the fact that nature no longer selects sperm – it is the embryologist in the laboratory who does this. ICSI bypasses natural selection of sperm (eliminates competition) because only one sperm is used.

The Australian researchers suggest that: ‘The possibility of treatment effects that are specific to ICSI is biologically plausible, although differences in male infertility factors that lead to the use of ICSI may also underlie the association.’

The following concerns have arisen from using ICSI:

- The risks of using sperm that potentially carry genetic abnormalities; it is thought that males eligible for ICSI carry a higher rate of genetic defects.

- The risks of using sperm with structural defects: although there is no absolute evidence that a physically abnormal sperm has abnormal genes, these sperm would not normally be able to fertilise an egg.

- The potential for damage (eg. from the needle or the chemicals used in the procedure), especially damage to the chromosomes.

- The risk of introducing foreign material into the oocyte: some culture media may contain heavy metals known to be toxic to sperm.

ICSI has been described as an experiment on a large scale, using children as subjects. This new research shows that too many children are bearing the brunt of the costs of this experiment.

These reports should be a challenge to clinics offering fertility treatments and to the regulator, the HFEA, not least in ensuring that women are warned of the risk of using ICSI. Are women being told of these risks? Is data being kept hidden? Is the use of prenatal diagnosis leading to more abortions after ICSI? When IVF and ICSI children grow up, will we perhaps see lawsuits and claims for healthcare costs against doctors and clinics?

Of course fertility treatments have brought the joy of parenthood to many thousands of couples facing the heartbreak of infertility. However, the costs that come with this are too often ignored by fertility clinics, and yet are paid for, with their pockets and potentially their children’s health, by couples desperate to conceive.