As of 10 June, for the first time in two and a half years, all three West African nations have been declared Ebola free and have remained that way for longer than 24 hours. As the two-year anniversary of my initial time in Liberia approaches, I have been reflecting on a blog post I wrote in September 2014 for the British Medical Association. I look at the journey God has brought me on since that time and I am astounded at all he has done in my life.

As of 10 June, for the first time in two and a half years, all three West African nations have been declared Ebola free and have remained that way for longer than 24 hours. As the two-year anniversary of my initial time in Liberia approaches, I have been reflecting on a blog post I wrote in September 2014 for the British Medical Association. I look at the journey God has brought me on since that time and I am astounded at all he has done in my life.

I no longer really recognise my life as it was before. As my colleague and friend, Bev Kauffeldt, who stood in the Ebola trenches with me often reflects, our lives are divided into before Ebola and after Ebola and there are few similarities. One truth remains: God is good all the time. He was good to us even through some of the darkest moments of our lives. We weathered the storm with him right by our sides.

On 14 July I travelled to Monrovia, Liberia, with Samaritan’s Purse International Relief to assist with the response to the Ebola epidemic. I had approximately 10 days notice and so had spent that time desperately trying to obtain time off work and gather the necessary essentials for the trip. The neonatal unit at Singleton Hospital, where I was working, were kind and granted me two weeks unpaid leave. At the time the Ebola epidemic had barely hit the news headlines but I had been following the situation since February-March time due to my interest in infectious diseases. It was very apparent to me during those few months that the epidemic was different from previous epidemics and was evolving on a rapid level.

When I was invited to travel to Monrovia I didn’t hesitate to volunteer. I knew it was where God wanted me to be. This may sound crazy to many; for me it was simple. If I didn’t volunteer, along with the many others who already had and would in the coming months, this epidemic was going to be completely out of control before the world woke up to it.

I could not sit knowing what was developing, and the level of suffering involved, and not act. Also it was an opportunity to work with a disease that most doctors only get to read about in their careers, an opportunity to gain further understanding of a pathogen I had long had an avid fascination about. So I got on a plane.

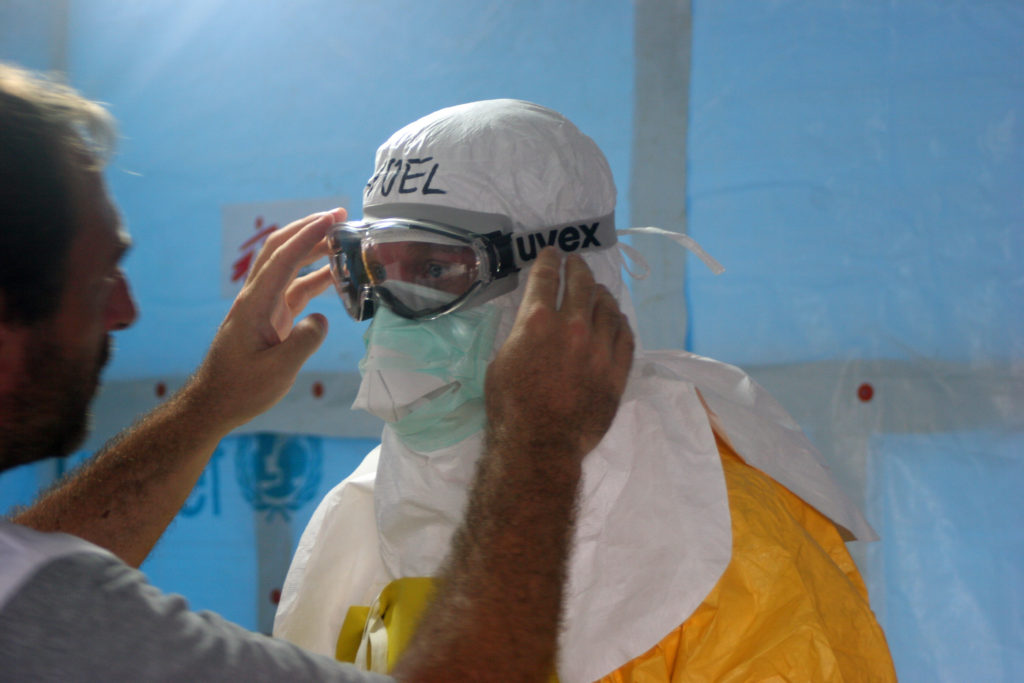

I knew before I went the risk I was taking and that medical evacuation in the context of Ebola was, at that time, essentially impossible. I knew if I contracted Ebola whilst working in Liberia I would likely die a painful and lonely death in Liberia. I had no experience of managing Ebola and no formal training in personal protective equipment (PPE) and decontamination measures.

I learned on the ground. I was trained by Dr Kent Brantly, Dr John Fankhauser and Dr Debbie Eisenhut, three US physicians who had been working in Liberia long before Ebola ever arrived. They had set up a small isolation facility at the ELWA mission hospital as they were acutely aware Ebola would at some point arrive on their doorstep; at the time there were no treatment facilities in Monrovia. At the end of June, Ebola did land on their doorstep and that is where this story really begins.

As I boarded my flight on 14 July, the reality of what I was doing finally hit me. I had to push a huge sense of apprehension aside. I spent the flight distracting myself with films and games but intermittently wondering what it would be like to manage patients with Ebola. I arrived late that night. The following morning I went to the small Ebola treatment unit (ETU) known as ELWA 1 – a six bedded unit developed in the small chapel belonging to the mission hospital; the only location they could create a proper isolation area. Two patients had arrived during the early hours of that morning, both of them had died by the time I arrived. One was surrounded by her own excrement, having collapsed in an awkward position on her bed. Later on that morning another patient died. I observed the PPE and decontamination procedures that morning and in the afternoon I put on PPE for the first time and entered the ETU.

I entered with three colleagues. We all had one purpose – decontaminate three dead bodies and carry them to the morgue, then clean their bed spaces in preparation for more patients. All three patients were women, two were my age and one was eight months pregnant.

So began a whirlwind two weeks in which we watched as the epidemic spiralled out of control. We received patients from more and more previously unaffected counties, knowing that following them would be more and more cases. We did all we could but we simply did not have enough resources. During my first week the Ministry of Health of Liberia asked Samaritan’s Purse to take over Ebola case management for the entire country. We had only recently taken over the ETU previously run by Medecins sans Frontieres (MSF) in Foya, Lofa county, to enable MSF to focus their attention on Sierra Leone and Guinea. We had been constructing a new 14 bed unit nearby known as ELWA 2. This was completed a few days after the request from the Ministry of Health. Unfortunately it was built assuming the government hospital in Monrovia would continue to manage Ebola patients in its ETU. When that ETU closed and the patients were transferred to ELWA 2 we found ourselves almost immediately over capacity. Over the week we expanded to 19 beds, then 25 beds. At the time of my leaving there were 28 patients in ELWA 2.

On 22 July Kent asked me to be the team leader at ELWA 2 to enable him to carry out administrative tasks. It was an extremely challenging day. I constantly juggled persistent phone calls with clinical work, as well as trying to unite a team of healthcare workers and hygienists suddenly thrown together by the amalgamation of two ETUs and employed by three different employers. This was interspersed with watching several patients haemorrhage profusely, admitting suspected cases through triage and trying to safely manage decontaminating patients whose tests were negative. Whilst we had a separate area for ‘suspected’ patients and ‘confirmed’ patients, our patients were often arriving so late in the disease process that they started to haemorrhage before we had a positive test result.

The following day I received a phone call where I was told Kent had a fever and had isolated himself in his home. From that point onwards I became the coordinator of the only ETU in Monrovia, with little experience of managing Ebola let alone running an ETU. That week is a blur of treating patients, managing relatives, coordinating blood testing and burial teams, managing team disputes and most importantly caring for Kent as he became increasingly unwell.

Sleep became a luxury I could barely afford. When I did sleep Malarone induced Ebola dreams invaded it. I no longer had any appetite. After 14 hours a day at the ETU I would return to shower and report figures for the daily situation report, receive phone calls with lab results and try and work out how we could expand the ETU to accommodate the-ever increasing number of patients. Every day I would arrive at the ETU and more of my patients would have died. There seemed no light at the end of the tunnel and any kind of control of the epidemic seemed increasingly out of our grasp. All the while Kent became increasingly unwell.

And then Saturday 26 July arrived. Initially I thought I was exaggerating, but on greater reflection I can now say this day was the worst day of my life. I had barely had four hours sleep the night before. I had risen early to take Kent and now also Nancy Writebol’s blood tests for Ebola. Nancy had been working with us as a hygienist in the decontamination area and had developed a fever the same time as Kent, although initially it was thought to be malaria related. All day long their imminent test results lingered at the back of my mind. I didn’t have long to dwell on them though. We had an impromptu visit from members of the World Health Organisation that unfortunately was rather negative, unhelpful and disruptive.

At the same time four patients died in the space of two hours, two of them bleeding profusely. One of these four patients was the well respected and eminent physician to the Vice President of Liberia, Samuel Brisbane. This created a political situation as well as a very emotional situation for my Liberian colleagues who were already struggling with the number of health care workers we had lost. These were health care workers they had studied with and worked with, people they would call not only colleagues but friends, people bound deeply by the experiences they had of working in an extremely under-resourced environment fighting for their patients lives.

They had continued to do this, despite Ebola, despite lack of access to PPE, despite the risks. They still cared for their fellow man or woman who was sick and some paid the ultimate price. These are the heroes of this epidemic, people who keep fighting when everything is against them who despite it all care deeply for their patients and are prepared to take an unfathomable risk. These people were not only their colleagues. They were my colleagues as well; they deserve the utmost respect for what they have done, not cheap criticism of their lack of awareness of appropriate PPE and decontamination procedures. The West has clearly demonstrated recently that even with all the facilities available, we get it wrong too.

That Saturday continued to get worse. We were rapidly knocking through walls to extend the ETU to accommodate an entire family of six patients travelling to us from Bomi county. Further new patients kept arriving at triage with no beds for them. Inside the unit many of my patients continued to deteriorate and the phone did not stop ringing with new patient referrals. Repeated phone calls to the burial team revealed they could not come to collect bodies from our overflowing morgue. There was dissent amongst the ranks in my team – understandable given the increasing burden of stress we were all under. Then that evening I heard a team meeting had been called. It brought the news none of us wanted to hear, both Kent and Nancy had Ebola.

It is difficult to put into words what happened next. The fear that we all had regarding what we were doing, the fear that kept us safe and that we kept at bay hidden under our PPE, suddenly welled to the surface. I have never experienced fear on that level before. It was a fear that paralysed us for a time and it resulted in completely irrational behaviour in some people.

When I woke the following morning I was unable to eat and drink. Fear was like a tight knot in my stomach. I went to the ETU to discover few national staff had turned up as well as there being an understandable reduction in our international staff numbers. A well respected local physician’s assistant had died of Ebola in the emergency room of the government hospital in the early hours of the morning. Understandably some of our local staff no longer felt they could work at the ETU. That day I was not sure I could either. Then I thought how could I ask my team to go in if I was not prepared to go in myself? More importantly there were patients who needed us. So I pulled myself together, put on my PPE and entered the unit.

Posted by Nathalie MacDermott, CMF member

Samaritan’s Purse is an international relief and development organisation providing spiritual and physical aid to hurting people around the world. Since 1970, Samaritan’s Purse has helped victims of war, poverty, natural disasters, disease, and famine with the purpose of sharing God’s love through His Son, Jesus Christ. Since 2008, we have provided assistance (including medical, among other forms) in over 108 disasters around the world.

Samaritan’s Purse is looking for Christian medical doctors interested in disaster and epidemic response to join their medical Disaster Assistance Response Team (DART) roster. For further information please attend our information evening on Thursday 21st July, 6.30-8.00pm at the House of Lords.

To register to volunteer with our DART teams please visit our website or email Cynthia Ryan